How to end DEI forever

Conservatives argue that diversity, equity & inclusion (DEI) programs need to end. I agree. Some may not want me to say this, but I know how to eliminate them for good.

Right-wing commentators frequently rail against so-called “woke” culture: a liberal plot to keep America from becoming the colorblind meritocracy it should be. More recently, Harvard alumnus Bill Ackman has pushed hard against DEI programs. But the core of it has been issues of diversity: from the problems with fighting antisemitism on campus to the very nature of Harvard’s DEI programs.

Some folks consider the topic a constant irritation. Consider this Instagram comment taking issue with me talking recently about America’s history of racism:

Why don’t everyone just quit talking about it all the time. Damn it happened what 200 years ago let the past stay in the past

I get it, man. It’s a drag. Racism, bigotry and hate are terribly uncomfortable things to talk about. Granted, it’s not an argument applied evenly to tough subjects. Imagine the outrage if someone said, “Jesus, every day it’s like ‘Cancer, this’ and ‘Cancer, that’… can we please not spend every waking minute talking about it?”

Except the cancer of bigotry is closer to being cured than ever before in American history. And we could be the generation that wipes it out. Ain’t that something to shout about?

Still, it’s not an entirely unfair question. Why don’t people quit talking about it so much? Why can’t the past stay in the past? Part of it comes from a sense that nothing is ever good enough for DEI advocates. They feel like there is an impossibly high standard America is being asked to meet, and anything short of that is unacceptable.

Where does that standard come from?

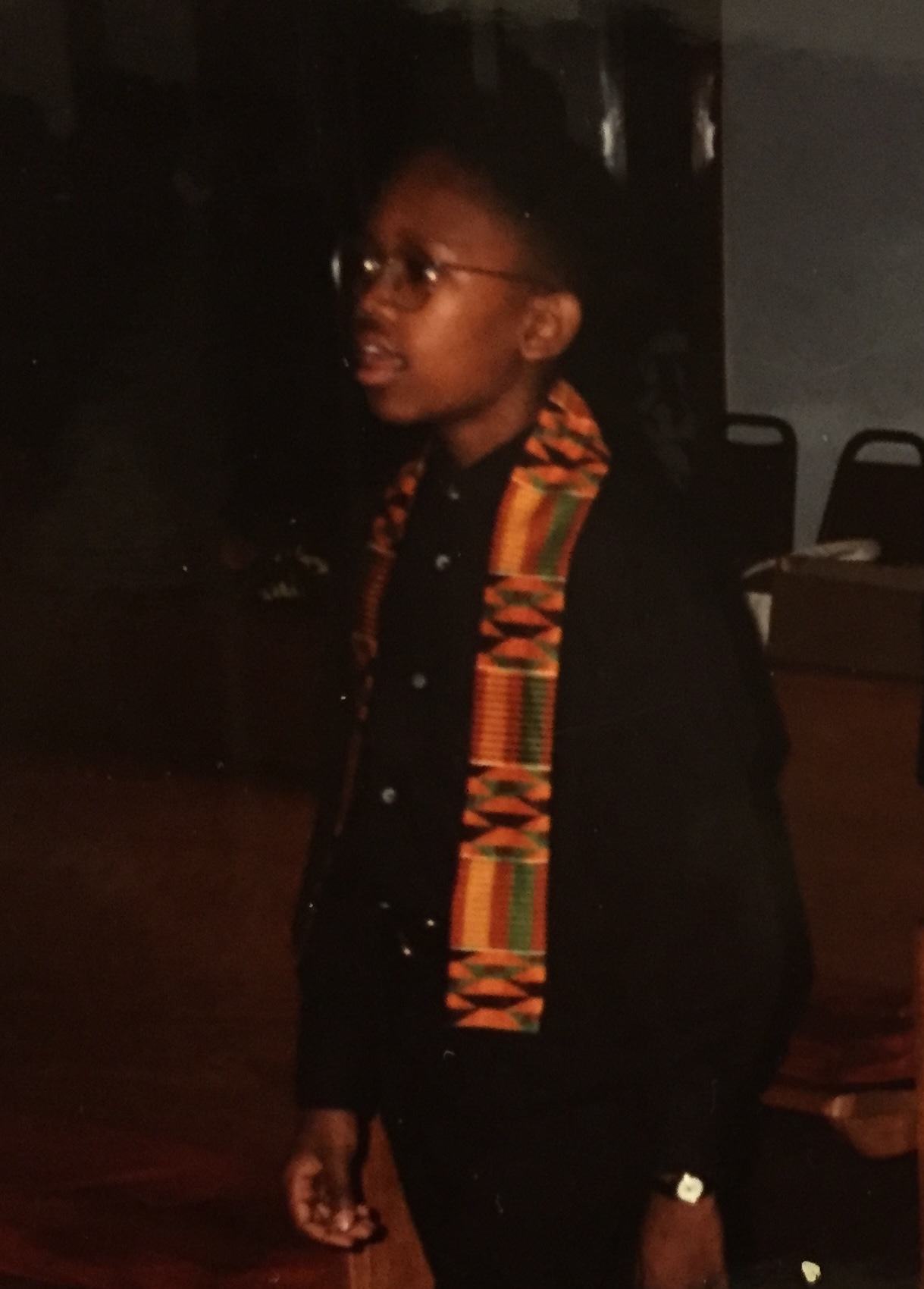

This kid knows. (Him and his big ears. Lord.)

I grew up in the early 80s, when Black culture and consciousness were evolving quickly. We had come through a time of civil rights and social awakening, surviving the tumult of the late 60s and riding a newfound willingness to discuss race in new ways. Norman Lear was about to give way to Bill Cosby & Arsenio Hall. CNN was about to show us the world, and BET was about to show us my world. Roots brought us to our knees, and hip hop got us on our feet. New challenges emerged including AIDS, crack cocaine and Pres. Ronald Reagan’s stereotype of the “welfare queen”.

It was a time of great promise, great problems and — here’s the key — great pressure.

What is “equity”, anyway? How do we know if “inclusion” is achieved?

When I was 7 years old PBS debuted Eyes on the Prize, a landmark docuseries charting the civil rights movement through the eyes of the people who lived it. I watched all 14 hours of it. My mother, a public school librarian, made sure I had access to that and any other materials about the Black experience I wanted. She felt this cause very deeply, having studied at Florida A&M University, an HBCU, during the late 60s. Mom was on campus when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, watching her classmates melt down with unresolvable rage.

I watched Eyes on the Prize in rapt fascination. It was like going back in time, but I knew the time travelers. Did Mom really go through that? Did my grandmother actually get treated that way? If this is what things were like then… what will they be tomorrow?

That’s why I was singing in the I.C.Y. (Inner-City Youth) Multicultural Choir, looking sharp in my kente cloth sash: to shape that tomorrow. I was learning all about my history and heritage, about Kwanzaa, about social justice, about my deep well of human value against the benthic depths of dehumanization. More practically I was learning how to present myself in public honorably and impressively. Presentation, coordination, elocution and obedience went a long way toward counteracting the stereotypes of Black people.

It took me a while to realize how resilient these lowered expectations were until it dawned on me how very articulate I was. Frankly, I didn’t realize what I was doing — just imitating the people on TV! But it drew two powerful reactions that made the imitation stick. Black elders took enormous pride in it. Whites expressed astonishment, sometimes bemusement. I don’t remember the day I realized that “You speak so well!” and “You’re so articulate!” were backhanded compliments borne of astonishment at the unexpected. I just remember it hurt.

But what could I do? Start talking more… ebonically? So non-Black people weren’t so stunned by me, and my Black friends would stop teasing me for “sounding White”? Is that the best I could hope for?

My uncle, King Wright, lived to be 98. I visited him often at Miami’s VA hospital, walking down long and winding corridors to the nursing home in the back. He knew I was working for The Miami Herald in its partnership with WLRN Public Radio. Every time he saw me he lit up, smiling warmly and laughing buoyantly. The joy he got from my work, in how I carried myself, in my good reputation — I wish everyone could feel that just once.

In a way, this pressure is healthy. It made me resolve to live the best life I could, because one day I could end up in the same place as him. If I spend my last days with little companionship but my thoughts, I want them to be warm memories, not icy regrets. That’s still my goal, and I’m still working on it, but I won’t give up. What I later learned — what poisoned this pressure for me — was that it doesn’t have to be this way.

White kids don’t usually feel pressure to succeed in life for the sake of all Whites everywhere. Of course not! Primarily that obligation was expressed by Mom and Dad, reflected in the social cues of their neighborhoods and communities. In that way, the idea of working hard and doing your best is a self-sustaining virtue. Diligence will bespeak your merit to others, and you will find success.

For many people of color, our pressure was not just familial — it was cultural. The opportunity had finally presented itself to elevate ourselves to something resembling equality. A new day was dawning, and we could be the generation to feel its full warmth for the first time. But the context was racial justice, and justice exists in the context of the crimes committed against Black people for centuries. Progress never rolls in on what Dr. King called the “wheels of inevitability”. (You can watch him say it here.) It takes work, and now I was working with tools and skills that my forebears could have never imagined.

Gone were the days when we hoped our simple good example would be enough to convince racists not to be racist. That idea of moral suasion came and went. Instead we didn’t have to behave in such a way that others would give us what we wanted — we could just make it for ourselves. We could counteract the images of Black failure with acts that conveyed Black excellence.

Getting straight-A’s was more than just a sign of my own smarts; it was a rebuke to the longstanding assumption that Blacks are less intelligent. Excelling at sports was more than just a display of ability; it was a rebuke to the stereotypes that kept Blacks out of leadership roles on all kinds of teams, athletic and otherwise. Speaking in public was more than just a powerful means of self expression; it was a rebuke to those who claimed most Black people had neither anything meaningful to say nor the skills with which to say it.

If that seems like an incredibly unfair amount of pressure to put on a child… you’re almost right. It’s an incredibly unfair amount of pressure to put on a race.

When you’re not part of a marginalized community (and I include economics in that as well as race), your life’s context is more likely to be about continuing a pattern. Prosperity preceded you; prosperity must follow you. Minorities have the opposite obligation: to break a pattern. Calamity pushed us down; you must lift us up.

When in doubt, tell your story.

This might clarify why some people denounce DEI programs as needlessly fixated on the past. Even Bill Ackman says he didn’t think antisemitism was that big a problem until the aftermath of Hamas’s attack on Israel. His context was dramatically different, until he couldn’t avoid talking about it. Well, guess who couldn’t avoid talking about racism from the day he was old enough to listen? Me, and every other Black child who grew up with me. Not because some woke social justice warriors were droning on about it all the time, but because our parents & grandparents told us. We, like many of my beloved Jewish brothers and sisters, were also admonished to Never Forget.

Frankly, I suspect many Black folks are carrying some trauma over all this. The stories of Jim Crow, images of lynchings and the spirits of dead slaves are inseparable from our existence. They give our story its richness and flavor, but that strange fruit has a bitter sting. How can that not leave emotional scars? And we’re so used to them that we probably think they’re normal. They’re not. No one should have to bear them. Future generations will, I hope, be born without them, but we’re not there yet. We’d love to be! But the sheer pain of our history still hurts. Generations died with the double despair of their own failure to change the world and not living to see us succeed… if success was even possible. And that despair, tinged with hope, cries out to us from the ages, urging us to speak in their memory:

You are charged with the highest mission of our people: liberation. We could not achieve it, but we laid a foundation for you. We cared for you, provided for you, prayed and cried for you, sometimes bled and died for you. Nothing is more precious to us than you. All we have is you. And now, we are counting on you to break the cycle, so that our people never go through this ever again.

If you spoke in the name of your grandparents… what would it take to silence you?

Your colleagues of color may be carrying layers of pain that they never talk about. What you might learn if they leveled with you might bring you to your knees. DEI programs are born of deep, generational traumas. These programs will end when those traumas end. I believe it can be done. Here are the three steps I would recommend.

First, everyone in this debate should make sure they’re actually having the same conversation based on the contexts they bring to the table. That means telling your stories to one another. Mr. Ackman and I may see DEI very differently, but it means so much to hear him talk about his father’s dying wish that he take antisemitism much more seriously. That pressure puts his words & actions into a meaningful context. Telling our stories humanizes us, and it eases the us/them nature of the debate.

Second, we should confirm that we mean the same things by the terms we’re using. I suspect lots of people aren’t having an apples-to-apples conversation about DEI. What is “equity”, anyway? How do we know if “inclusion” is achieved? Clearly defining the problem is key to scientific inquiry, and I think social inquiry requires something similar. Reaching consensus on these terms helps to keep your larger debates productive and brief.

Here’s my way of thinking about DEI: Diversity is just variety. Equity is accountability. Inclusion is community. You need all three to have a sense of belonging and security.

Disability advocate Jamie Shields put it another way: “Equality is everyone getting a pair of shoes. …Diversity is everyone wearing a different type of shoe. …Equity is everyone getting a pair of shoes that fits them. …Inclusion is feeling respected and valued whether you are wearing shoes or not.”

Third — the not-so-secret secret to eradicating DEI forever — work together and solve the damn problem. Just get it done. Drop the politics, debate solutions, try new things and for God’s sake, give social media a rest! Just do the work. There’s a lot of money to be made by whining about the problem, and some people won’t be willing to give that up. Step over them, and keep working. Struggle towards a solution.

Every day you spend attacking people on the other side of the issue (whatever side you’re not on) is a day wasted. That’s another day we hear those distant voices, the stories of our grandmothers, the pressure of our people, and they will never stop crying out until we all get this done. There is one and only one surefire way to end Diversity, Equity & Inclusion programs: make America diverse, equitable and inclusive.

Remember that DEI programs are not merely about peaceful workplaces free from conflict. They’re about breaking cycles. They’re about disruption and redemption. DEI is for all the kids who were told about migrant farmworkers and Holocaust victims and Marsha P. Johnson and Emmett Till and internment camps and indigenous boarding schools and burst into inconsolable tears, wondering how anyone could be so evil to another person.

Refusing this task means you don’t actually want a meritocracy. You want peace and quiet. If you believe in judging people by their hard work, but you won’t do the hard work of creating a true meritocracy, then what does that make you?

Bigotry is as horrid as dehumanization. The idea that anyone would think their skin makes them a better person is moronic, and it’s just as toxic as living in a world where your skin color makes you fare worse. Perhaps that’s the first step on a new path forward: owning the interlocking awfulness of our pasts. When in doubt, tell your story. We all have cycles to break. We will break them faster if we do it together… and do it now.

Joshua: This is just brilliant. I have forwarded to friends. I would love to see this published in newspapers in opinion sections. I think your perspective is so valuable; it's hard for me to keep up with all you've written but everything I see is thoughtful. Keep up the good work.