He lashed out at a kid. Little guy’s been crying all morning.

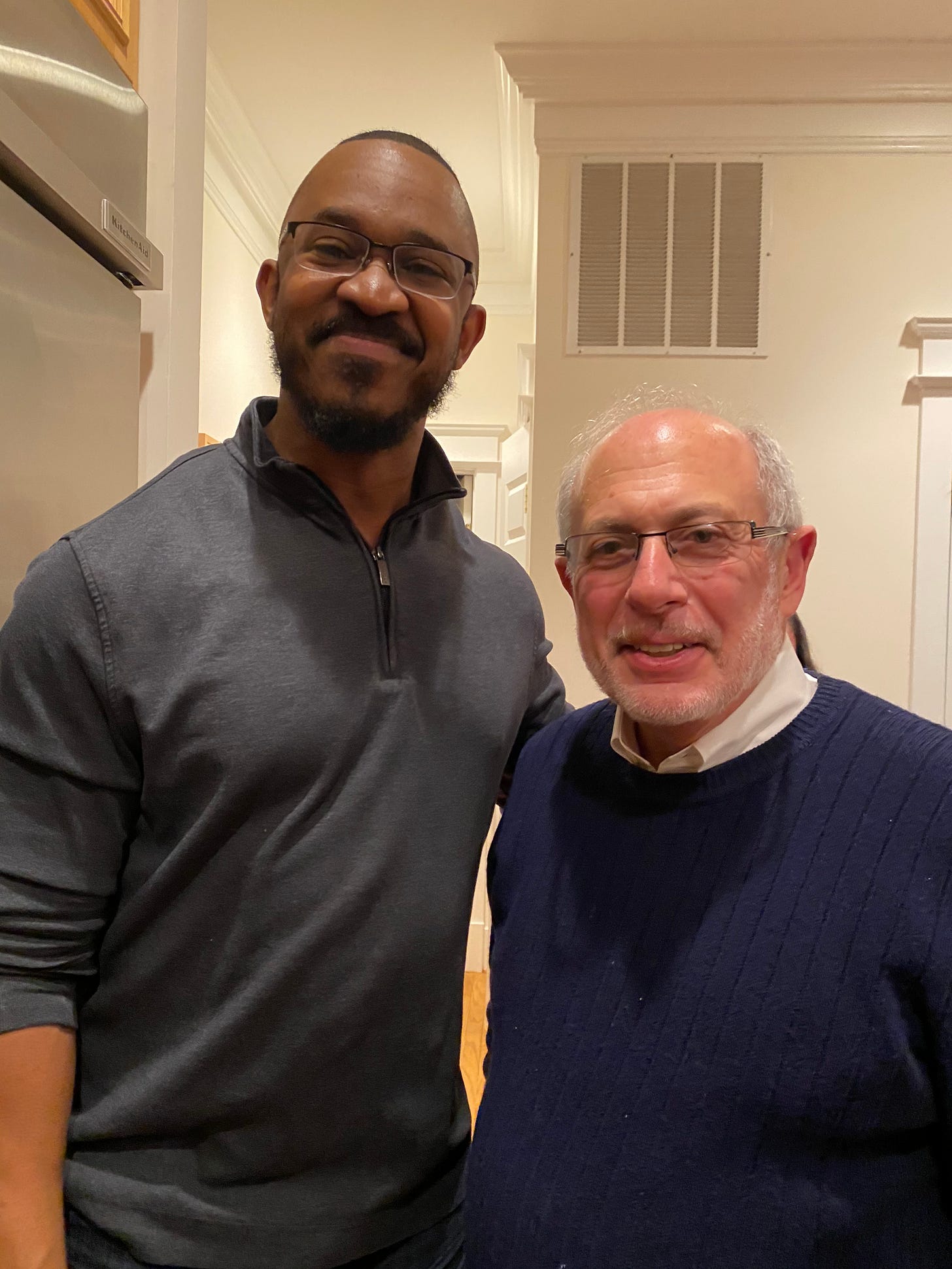

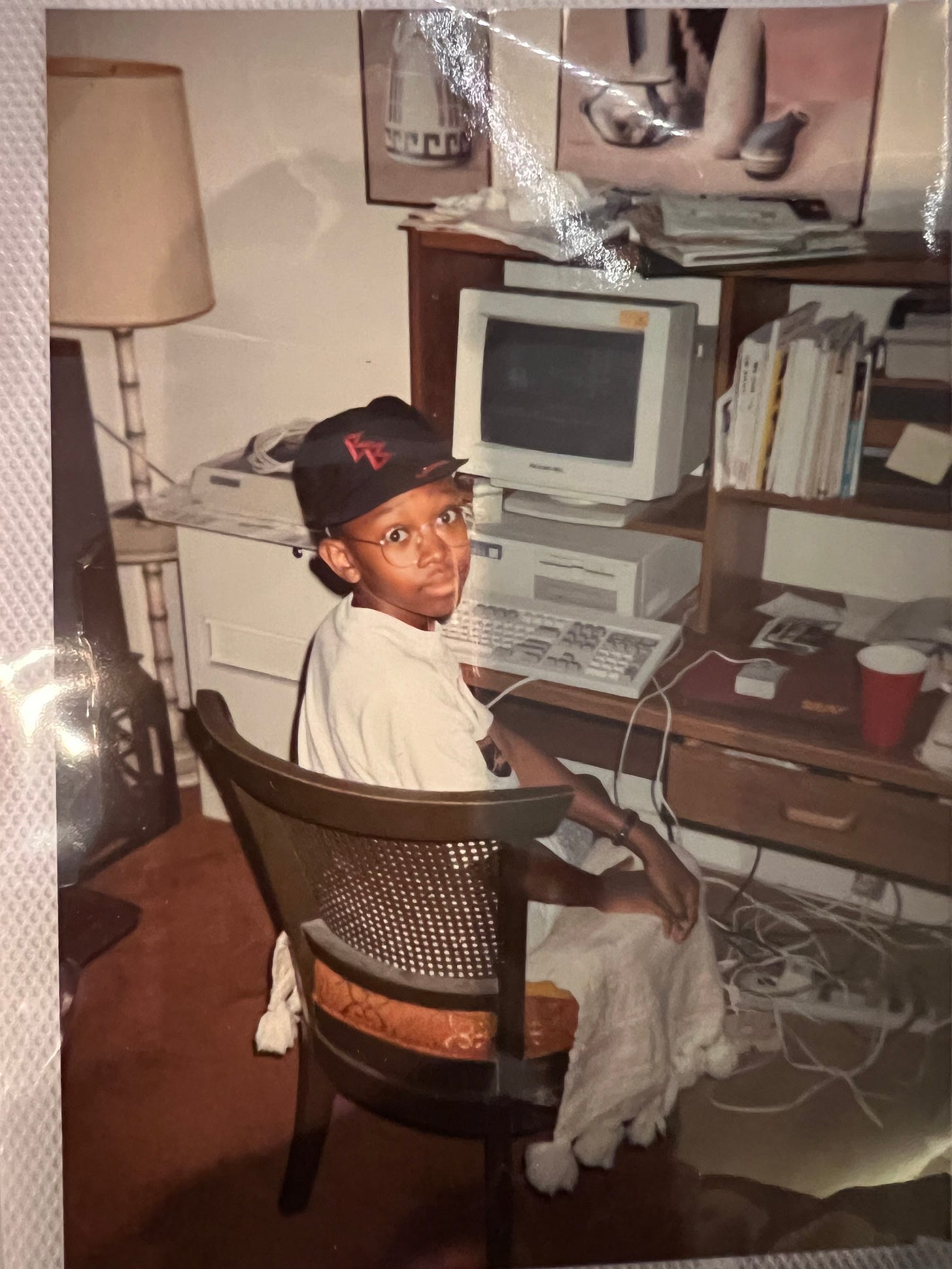

Everyone told me I sounded White. When you’re a skinny nerd trying to make friends it’s amazing how cruel that can sound from other Black children. I didn’t ask to be this way: to love reading, to have a natural gift of gab, to be so curious as to be a bit of a pest. Fortunately, my mother loved that pest. Encouraged him, even.

I don’t know the first time I heard Robert Siegel’s voice. Probably when we were in Philadelphia for the summer, and Mom was listening to Temple University’s WRTI. Today it’s an all-jazz station, but at the time it played news as well. All Things Considered tickled my ears with all its suavity, precision and brilliance. It fired my imagination and captivated my attention, even as a kid of 13 or 14.

NPR made me feel like I belonged somewhere.

Perhaps Mr. Berliner, a longtime editor at NPR News, has forgotten the power of what he’s spent a career doing. For many of us, it’s not about information. It’s about validation. NPR member stations have spent decades building communities of people just like you — whoever you are — and proving that they hear you by telling stories about the expanse of human life. I heard few Black journalists on the network at first, but that improved over time. What I did hear were curious, precocious, thoughtful, interesting people who cared about knowledge and shared it with everyone.

That kid had already found his voice. In NPR, I found a place to use it.

Yesterday I reacted to Berliner’s piece in

, and his podcast interview with , as thoughtfully as I could in a segment on NewsNation. This morning my tears were hot and violent. I was shaking with rage, silently screaming, as if a loved one had been killed.I spent six years as an anchor/reporter at WLRN in Miami, six more as the morning newscaster at KQED in San Francisco, and three at WAMU in Washington as the founding host of the NPR talk show 1A. For much of that time I was a stressed out, overworking, perfectionistic, insecure, overwhelmed ball of nerves. Sometimes I look back at the man I was then and cringe at how much growing up I had to do. My colleagues deserve hazard pay, with interest. Still, I don’t know how I would’ve become the journalist, the interviewer, the creative artist or the person I am today unless I’d found public media.

NPR member stations are as flawed as any human endeavor, and many have a lot of growing to do. But you will rarely find a company with such loyal, invested clients. People don’t just listen to it. They “love” it. NPR’s relationship with America is precious. No wonder it’s always attacked: lots of people would love to bring it down, because they can’t measure up.

So it’s easy to see why so many of NPR’s haters showed up when Mr. Berliner vomited his frustrations in the gutter outside 1111 North Capital Street. It was just what they’d been scavenging for: proof that those liberal lefties who thought they were so special really are as woefully woke as we thought. They were a disgrace to the people who started NPR, a betrayal of its values, proving that the whole organization doesn’t deserve our trust and should be left to rot. Berliner’s arguments ranged from the network’s coverage of Trump-era controversies (COVID, Hunter Biden’s laptop, etc.) to its apparent groupthink on DEI issues.

He may have a point. Unfortunately, that’s not what matters most.

Uri Berliner didn’t just attack NPR. He attacked a community. His article denigrated a nationwide chosen family, bonded by their love of learning, their civic duty and their belief in doing good. Perhaps he joined this community for the right reasons but, having stayed in it for so long, he forgot why he showed up.

His screed laments NPR’s current condition, from his perspective, but it makes no suggestions of how to fix it. He lays out how he’s raised his concerns internally, but says nothing about any stories or projects he pitched to actually improve things. 25 years at NPR should’ve given him some insights on how to make things better, but none emerge. Then again, if all you want is to see him vomit in the street, solutions would kill the vibe. And now the stench of it will drive people further away, including some who may have truly legitimate complaints about NPR.

I’m no apologist for this or any network; I believe every news organization has a hellacious amount of work to do in meeting this moment. Nor am I blind to the complaints about tone and bias. Since leaving 1A I’ve gotten lots of online comments lamenting the program’s current tone. I haven’t listened in a while, but my former listeners tell me that it felt more balanced and incisive when I was the host. Whether they’re right or not, I don’t know. Regardless, we should always examine our work, hunt for areas of improvement and be humble in the face of reasonable critiques.

But denounce it? Destroy it? You’ll have to get through me first. I’m not the only kid who needed to feel like he belonged. I’m not the first person to wonder if he was cursed to be an outsider: the only Black kid among my White friends, the only gay kid among my straight friends, the youngest kid among older friends, the oddly erudite kid who couldn’t really jell with almost anyone. Deeply pensive, wildly creative, preternaturally passionate… I cannot be the only one who felt like a hybrid too strange to live.

And then Robert Siegel spoke to me, without knowing my name. He may have saved my life.

I trust NPR, but if anything would make me not trust it, it would be that its journalism is edited by people like Uri Berliner. The ultimate way to break my trust would be to have people in its headquarters who’ve grown so entitled and comfortable, who are so embittered and cynical, so blinded by their own malaise and so blind to the opportunities before them, that they’ll publicly shame their team for… well, for not much. I hope the catharsis was worth it, now that he set his house on fire.

The real shame of it is that Mr. Berliner may actually be raising some legitimate points about NPR’s biases. Every human being has biases, so the idea that NPR is truly unbiased is fanciful. The key is recognizing your points of view so that you can work around them as needed. But what’s the point of having that conversation with someone who’s proven himself not to be an honest broker? His article demonstrates that if he doesn’t get his way, he’ll give up and shame you publicly. And that was done with no clear path forward to getting what he says he wants.

The conversation about media bias is absolutely worth having, especially with NPR’s fans who love this community so much. I have my idea for advancing that conversation, and I’m open to others. But if 1A taught me anything, it’s that tough conversations only work in a space where everyone is free to be themselves, and where everyone upholds that freedom for everyone else. Mr. Berliner, you claim that ideological biases are hurting NPR. But your own ideological biases led you to hurt NPR. How can we trust you now?

The petulant child in me wants to see Uri Berliner face consequences for all this but, let’s be real: 25 years at a national news network have probably insulated him enough financially that firing him isn’t much of a threat. It’s not like he’s unemployable; a number of outlets would probably hire him, especially those that disdain NPR.

So, what should we do about this… and about him?

My experience in public media taught me to look well under the surface of what people present to you, and search for what’s not being said. It would be easy to denounce Mr. Berliner as a crank or a mole or a turncoat or something like that. Regardless of what he is, I don’t see why he would do what he did unless he was in real pain. And pain makes people do strange things. Whatever led him to this point, I hope he can make peace with this part of his journey. Perhaps some of that peace will come from knowing that, despite the network’s issues, he and NPR have done a lot of good for a lot of people: including a bright-eyed Blerd from West Palm Beach, FL who just wanted to feel like he belongs.

Perhaps that’s at the heart of all this. Maybe Uri Berliner felt like he belonged at NPR when he got there, but over time he felt more at odds with it in ways he could no longer tolerate. In his piece he describes working there as “as source of great pride”, and he calls the network “a place I love”. His sense of estrangement apparently became “uncomfortable, sometimes heartbreaking.” But that’s only about 1% of the article. The rest reads like a federal indictment. What a shame that he stayed in his head, perhaps too nervous to let us into his heart.

Now is the time for everyone who truly cares about public radio’s future to dig into all its challenges, right now. Even our biggest fans are worried about perceptions of bias, and they deserve to be heard. But let’s not deal in generalities; let’s get specific. Show up with links to articles and audio pieces. Don’t tell me there’s a problem: show me. Be specific, explain what bothered you and — here’s the key — offer an idea to improve. It doesn’t have to be perfect, but give us something to work with.

NPR member stations are also struggling financially, with cutbacks and layoffs at some of the system’s largest stations. Podcasting is increasingly competitive. A.I. is going to… maybe destroy everything? There’s plenty of work to be done. If you really care about the future of NPR, dig in. And stations: if this happens then you’re in for a lot of uncomfortable conversations with the public. Take them as a blessing. If a reasonable person is willing to get honest with you about their concerns, then hopefully that means they care about seeing those concerns addressed. Don’t miss the opportunity to turn a critic into a member.

That’s how I know who to listen to about the future of NPR. Vultures have always circled over the network, and their flight patterns haven’t changed, so I know exactly how to shoot them down. They bore me. What fascinates me are the people who circle around the network, protecting it and improving it. What builds credibility is not the reform plan but the love it’s imbued with.

In other words: we don’t care how much you know, until we know how much you care.

So, Mr. Berliner: what would you say to him?

I am confident you didn’t mean any of the harm that your article has caused him. You didn’t know the kid, even if you did make him cry. Things happen; life’s rough sometimes. But now that you know about the harm, how do you respond to it? Will you double down on your argument, or will you be present in this moment and deal with what’s before you? Will you hide behind the fortress of your facts and figures, or are you brave enough to be vulnerable with the people you insulted? Can you stop being an editor, a manager, long enough to just be human?

I have tried very hard in recent years to get rid of that kid. He doesn’t know how to reconcile his iridescent ideals with the matte-black morass of reality. He feels too much, hurts too deep, loves way too hard. Before that piece came out I thought I was on a pretty good path toward releasing him forever and moving on with my life.

Perhaps it’s for the best. My search for belonging never really ended, and it’s helpful to understand just how much NPR factored in that search. For all their faults and challenges, I owe WLRN, KQED, WAMU and every single member station an enormous debt of gratitude. And maybe, in a twisted way, Mr. Berliner did us a great favor, giving us this moment to take stock and ask tough questions. This doesn’t have to be a moment of decline. It can be an opportunity to rise, without flinching at the ugly spots and without downplaying the awesome beauty of what we’re building. I’d like to help, in place of that kid. He was a good little guy, but God bless him, he only knew how to dream, work and cry.

Thank goodness he taught himself to fight.

You know, a lot of your stories as a young blerd resonate with me. I was a private school brat - all but my senior year of HS were at Catholic schools - but I encountered that same feeling of social isolation, that same confusion when people seemed so hostile to knowledge and truth, and so confused because why wouldn't people care about those things? If you don't care about those things, how can you know anything else to be correct?

And like you, NPR has long served as a panacea for a lot of that - knowing there was a cohort that cared about those things, and did their best to serve them.

I'm reading this piece as part of Parker Malloy's recommendations around the whole thing, and I find it thoughtful and true and seeing a problem I see in a lot of other places. Parker also linked Alicia Montgomery's piece over on Slate - https://slate.com/business/2024/04/npr-diversity-public-broadcasting-radio.html

And that one I think really hit the head on a lot of this, especially the DEI bits which I have seen mirrored in corporate America in my time there. Those in power are afraid to be uncomfortable, terrified of the repercussions of saying or advocating for the wrong thing, caught up in a web of social games because everyone is always chasing the next advancement - as if you aren't, you don't go up.

But even with that - places like NPR remain important. Because they give us weird kids something to look up to, something to hope at - and when inevitably we find out, later, that it doesn't live up to our dreams...well, some of us, a precious few, decide that they will do the work to ensure the place lives up to the dreams of the next kid.

And a precious few of those precious few actually succeed.

I don't think you should let go of the kid still in you. If it's like mine - yea, she hurts a lot. She wants to cry a lot. But that pain, that anxiety, all of that comes because she still sees the better world, still dares to dream, still believes in the hope that that better world can come to pass.

And if I let her go, I may free myself of her pain, but what do I lose in sacrificing her dreams?

I am an adult convert to Roman Catholic, so I can feel some empathy for your reaction to being told that a beloved institution has feet of clay, perhaps mixed with a bit of dung. My wordsmithing is of a different sort than yours, but I admire your craft. That said, I think that you have ignored 3 specific, pretty well documented, criticisms of NPR's bias in Berliner's piece. Yesterday (IIRC) I was listening to NPR - I really don't recall if it was ATC or The World, but I think it was ATC. There was a bit about how Republican were parroting Russia propaganda about Ukraine funding and how dangerous that was (tone and shading of Trump/Russian collusion to my ear). Next up, with no sense of irony, was NPR parroting Hamas propaganda about Israel and genocide.

Berliner picked 3 examples - and the importance of the Russia hoax was demonstrated yesterday. I went back to review your Clinical Journalism piece which you linked, to make sure I was seeing your whole perspective. Early on, you touched on the "fine people" meme. Even Politifact wouldn't let that one pass, though they tried to pass it off as context and timing. https://www.politifact.com/article/2019/apr/26/context-trumps-very-fine-people-both-sides-remarks/

The common worldview of NPR has let some pernicious weeds grow in the garden of civic discourse. I hated it when my church got caught up in pedophilia charges. I hate it for NPR. Killing the messenger isn't the helpful response, however. Because I admire you, I am not withholding from you what I believe to be truth. Not only because the truth shall set you free, but also because people you respect are entitled to the truth. Correct me if I am wrong, of course.